A European carbon border adjustment constitutes the first step towards a fair competitive situation for emission costs. This goal defined by the European Commission cannot however (yet) be fully achieved. This aspect, together with other potential effects, is discussed in the policy brief “Implications of a CO2-border adjustment for international trade – analysis with a focus on the iron and steel sector” by the Institute of Energy Economics (EWI) at the University of Cologne.

In July 2021, as part of the “Fit for 55” package, the EU Commission presented a legislative proposal for such a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) for the particularly CO2-intensive sectors aluminium, fertilizer, steel, iron, cement and electricity. According to this proposal, importers of products of these sectors manufactured outside the EU would have to purchase CBAM certificates. The number of certificates would be based on the emissions (directly) caused during the production process. The aim is to create a “level playing field” of emissions costs — a market with fair competitive conditions — for all companies.

This must be seen in the context of differing ambitious climate policies worldwide. For example, if the CO2 price in the EU is higher than in a non-EU country, there is a risk of “carbon leakage”: companies that have so far been based in the EU could relocate their production to countries with less restrictive climate regulations to avoid the (higher) CO2 prices. This would merely shift emissions, and possibly even increase them due to less strict regulations.

The EU Commission plans to determine the CO2 footprint of goods only based on direct emissions released during the manufacturing process. Indirect emissions, such as emissions from the extraction of raw materials, their processing and the generation of electricity, heat or gas, which are necessary for the production process, will initially not be taken into account in the CBAM.

The CBAM price can be reduced by a CO2 price which was already paid in the country of origin. Currently, the majority of the most important EU trading partners have not implemented (comparable) CO2 pricing in the CBAM sectors. Thus, exports to the EU are expected to become more expensive. For European producers, on the other hand, an increasing price of CBAM-imports may make it attractive to meet the EU’s market demand themselves and replace (previous) imports to the EU.

EU producers must bear costs for indirect CO2 emissions through the EU emissions trading system (ETS), for example for higher electricity costs. In the future, EU producers will no longer be allocated free CO2 allowances via the “carbon leakage list.” To what extent national subsidies (e.g. the German electricity price compensation) will remain in parallel is currently open. “Thus, not taking indirect emissions into account in the EU-CBAM leads to distortions in competition and could weaken the international competitiveness of EU producers,” points out Senior Research Consultant Eren Çam, who co-authored the policy brief with Lisa Just and Patricia Wild. The EU-CBAM is a first step in the right direction but can presumably not (yet) fully achieve a global level playing field.

The extent to which exporters are affected and their options depend on various factors:

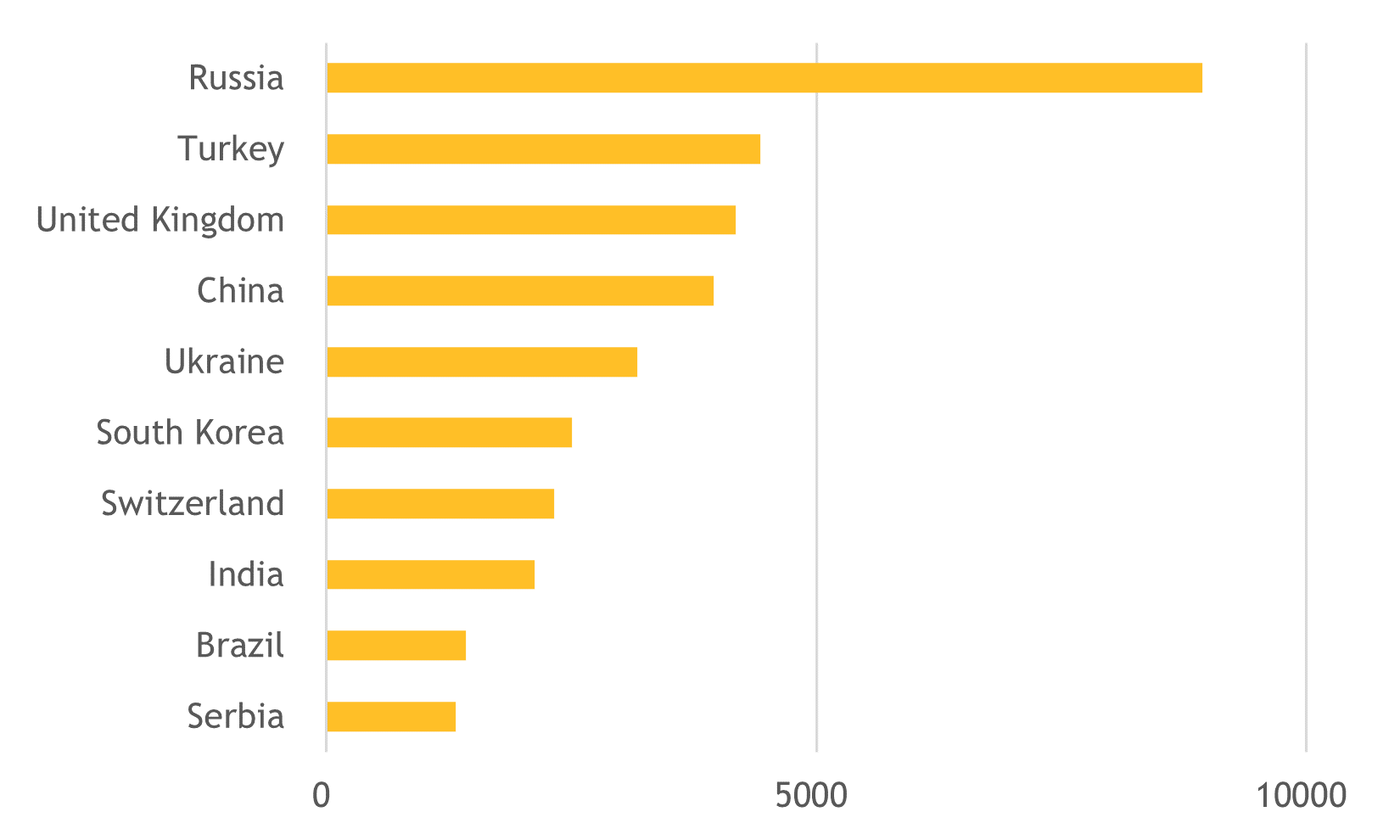

Producers in Russia, Turkey and Ukraine, especially in the steel and iron industries, are expected to be most affected by the CBAM. “They currently have high export volumes and no or a low CO2 price,” Çam says.

Producers affected by the EU CBAM have several options to avoid or reduce the additional costs of their exports to the EU: