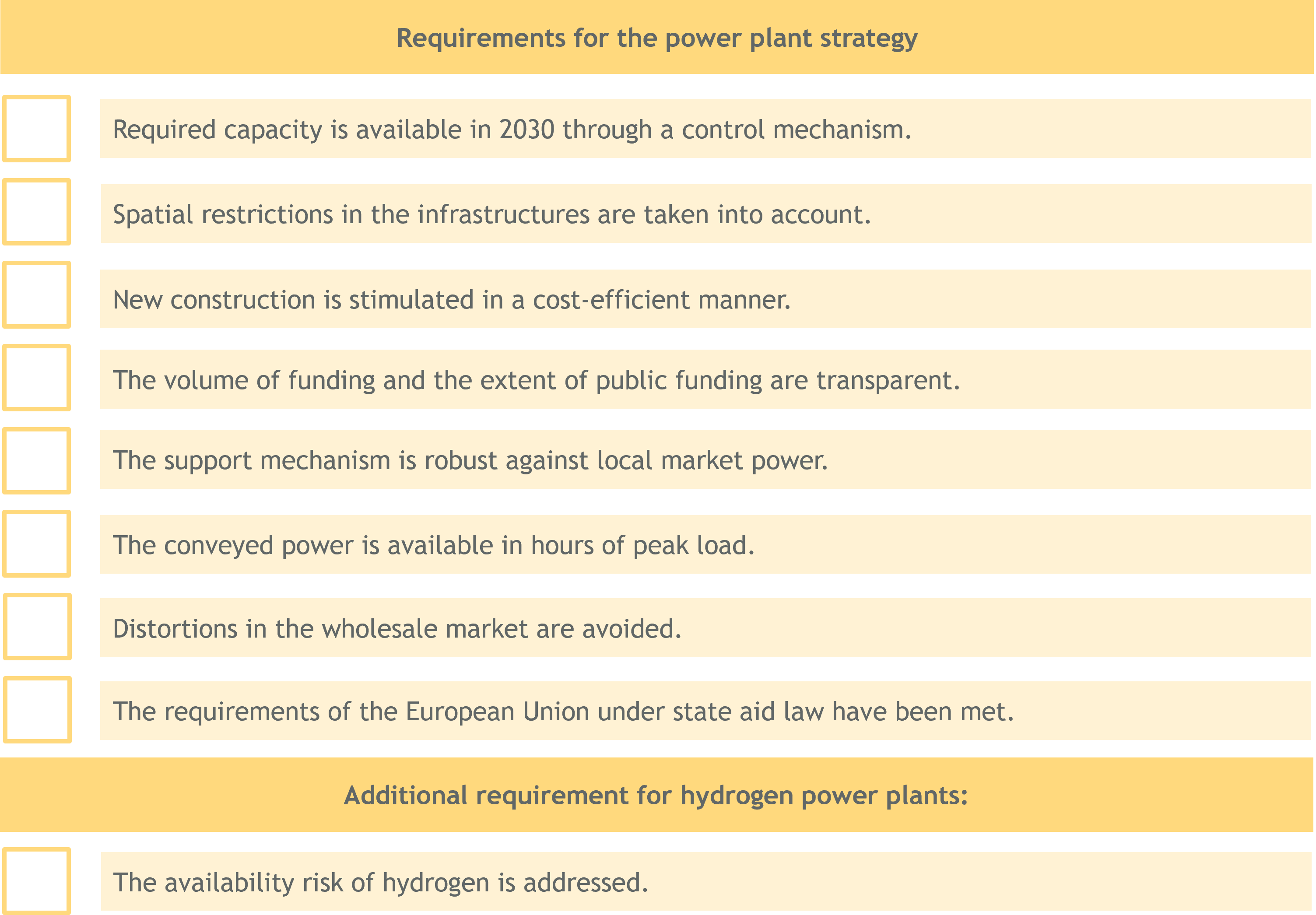

The German government has announced its “Power Plant Strategy 2026” for summer 2023. This strategy aims to build up to 25 GW of controllable power plant capacity by 2030. The funding instruments required for this have yet to be defined by the federal government. The Institute of Energy Economics (EWI) at the University of Cologne has summarized the key requirements for such a strategy in a checklist. This allows the announced power plant strategy to be held against these requirements as soon as it has been published.

In the policy brief “The Power Plant Strategy 2026: Goals and Challenges,” EWI publishes the checklist, and an EWI team also discusses the goals of the power plant strategy and analyzes the individual components based on the information already available. For a successful power plant strategy, several criteria emerge that should be met. For example, the power plant strategy should take into account where and when which power plants are needed, incentivize cost-efficient new construction, and determine the necessary subsidy volume and public financing. The chosen support instrument should ensure incentive-compatible behavior of the supported power plant operators while avoiding distortions in the wholesale market.

The power plant requirement of 25 GW mentioned by the German government results from an expected increase in electricity demand and peak loads in this decade and as a replacement for coal-fired power plants as part of a coal phase-out path. The exact extent of these developments depends on a variety of factors and may increase or decrease real power plant requirements by 2030.

The German government plans to implement the planned expansion mainly through hydrogen power plants and hydrogen-capable gas-fired power plants. The power plant strategy needs a mechanism to respond to uncertainties and deviations from the plan.

In the electricity grid, there are currently structural bottlenecks in transmission from northern and northeastern Germany to southern and western Germany. This requires the addition of power plants primarily south of the grid bottlenecks. According to current plans of the long-distance grid operators, however, a hydrogen grid would be expected primarily north of these bottlenecks, so that a location in northern Germany would be optimal for this type of power plant. These and other restrictions result in a coordination task for the system-optimal location of the power plants.

The central element of the power plant strategy is to promote new hydrogen or hydrogen-capable gas-fired power plants. “A key element of government support mechanisms is the assumption of risk by the government in order to increase investment,” says Dr. Philip Schnaars, manager at EWI, who prepared the policy brief together with Hendrik Diers, Philipp Artur Kienscherf, Henriette Nalbach and Pia Willers. The subsidy mechanism chosen for this purpose must ensure cost-efficient new construction in order to keep the level and distribution of costs as low as possible. A market-based mechanism such as auctions lends itself to this.

In addition to cost-efficient expansion, the subsidy instrument should ensure that the installed capacity is also available for power generation and that no distortions occur in the wholesale market. In this context, the requirement for precise location can lead to lower cost efficiency because market power can arise in auctions. “The power plant strategy must strike a balance between these different requirements,” Schnaars said.