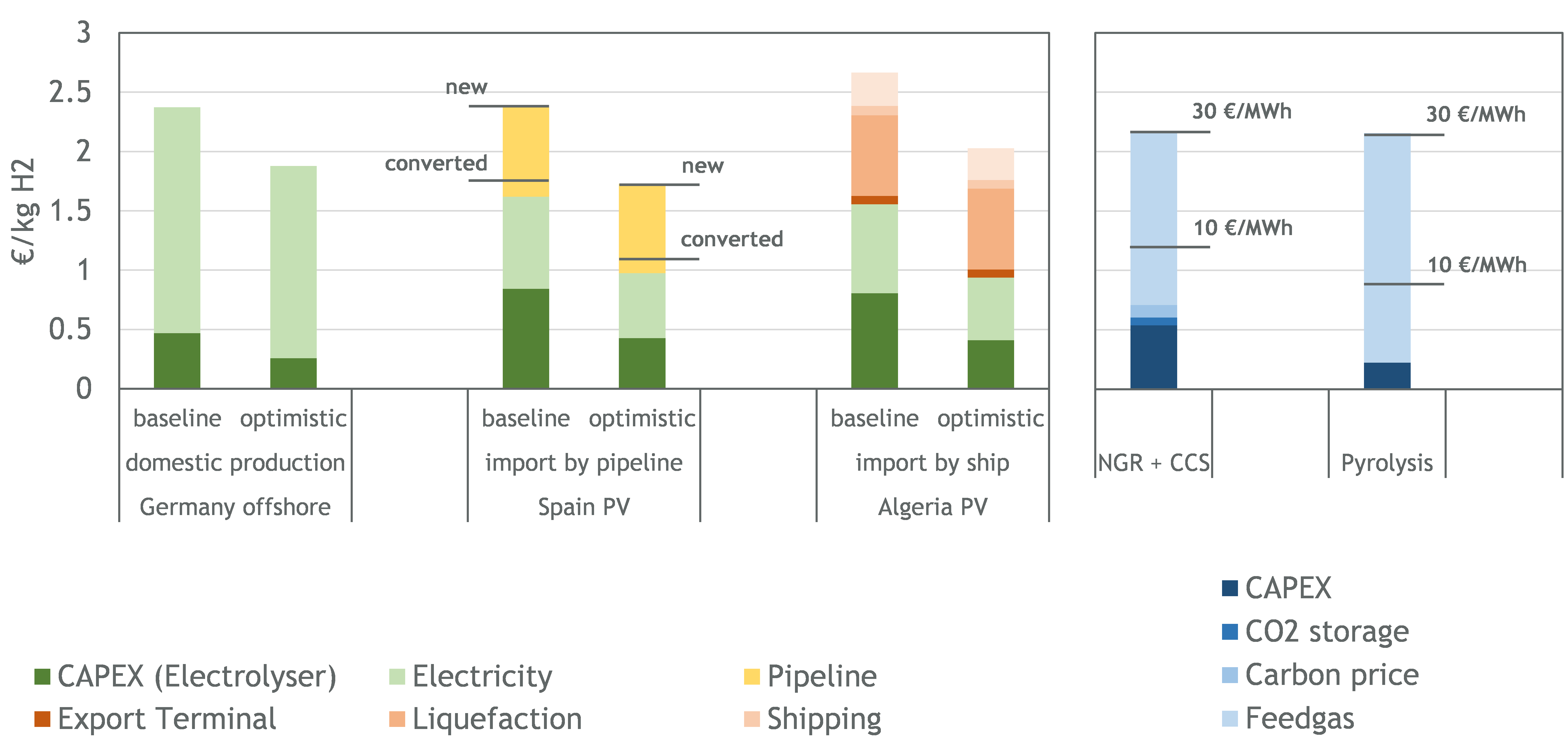

The costs for the production of green hydrogen show a high range worldwide. Hydrogen can be produced by electrolysis at the world’s best wind or solar sites about 40 percent cheaper than in Germany. This is due to the poorer potential for renewable energies in Germany. However, importing it to Germany is sometimes associated with high transport costs. If the hydrogen is transported by ship, they are about the same order of magnitude as the production costs.

“Overall, depending on the scenario, importing green hydrogen is only cheaper than domestic production if it is imported via converted natural gas pipelines from countries with high solar or wind potential,” said Max Schönfisch, Research Associate at the Institute of Energy Economics (EWI) at the University of Cologne, at the launch of the new EWI Insights digital workshop series. “In that case, the advantage of lower generation costs abroad in Spain or Norway, for example, would easily outweigh the disadvantage of higher transport costs.”

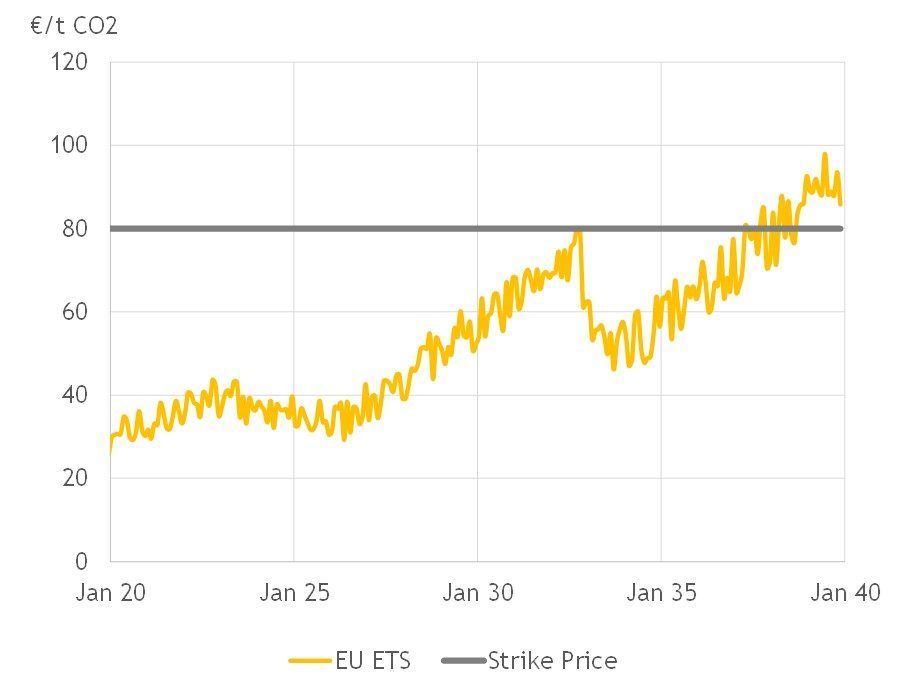

For Germany to become climate-neutral by 2050, industry must also play its part in decarbonization. At present, however, some key technologies are not yet technically mature. This leads to uncertainties regarding additional costs and the profitability of investments. EWI Research Associate Samir Jeddi presented an instrument that the government could use to support industry: the so-called Carbon Contracts for Differences (CCfDs). These are also part of the German government’s National Hydrogen Strategy. The aim of this instrument is to hedge price risks for CO2 certificates and thus reduce financing costs for companies.

CCfDs are contracts, for example between the state and a company (e.g. a steel producer), in which both set a price (“strike price”) that ideally corresponds to the company’s CO2 avoidance costs for an investment. If the realized CO2 price in European emissions trading is lower than the strike price, the company receives the difference from the state. If, on the other hand, the realized CO2 price is higher than the agreed strike price, then the company pays the difference to the state.

“However, CO2 price risk is only fully hedged by CCfDs if the CO2 price is fully passed on to end users,” said Samir Jeddi. “This is only partially possible in most industries due to international competition and heterogeneous international CO2 pricing.” As a result, companies may be “over-hedging” themselves, he said. The CCfD would thus change from an instrument of risk hedging to a (partial) speculative position, thus thwarting its actual objective. The precise design of CCfDs was therefore crucial. At the kick-off of the EWI Insights event series, nearly 100 participants discussed hydrogen sourcing options and funding instruments. EWI Research Associates Max Schönfisch and Samir Jeddi presented current research results of the EWI. The event was moderated by Dr. Simon Schulte, who heads hydrogen research at the Institute. The new online workshop series will take place about four times a year and is aimed at professionals from business, academia and politics who are interested in scientific findings from the world of energy.